Katherine Carras is a recent University of Waterloo grad in Systems Design Engineering. She works in Silicon Valley as a product designer at Palantir Technologies.

And she’s got a message for would-be tech employers in Waterloo Region: Get in the game.

U.S. companies, Carras says, recruit university students much more aggressively than Canadian ones. They identify talent nearing graduation long before most Canadian companies do. They routinely offer guaranteed jobs as much as a year before students are scheduled to finish their programs – scouting students with targeted, exhaustive savvy, much the way pro sports teams scout college players – and they pay much, much more money.

“I don’t think there’s an unwillingness among Canadian grads to stay in Canada,” says Carras, 23. “I think a lot of it comes down to the cadence of opportunity. A lot of international and American companies – specifically, American – will recruit new grads very aggressively early on in their last year [of university].

“I wanted to stay. My family is [in Canada]. I want to contribute to [Canada’s] economic growth.”

But when Palantir, a big-data analytics company with an estimated market capitalization of $20 billion, showed up offering a good, high-paying job a full year away from her graduation date, it was impossible for Carras to say no.

And when Canadian companies came calling months later? Well, they were way too late.

Carras’ experience is hardly uncommon. Many of her classmates have made similar decisions, as have those from countless graduating classes from across Canada, prompting much high-level debate over what to do about the “brain drain.”

What is uncommon is hearing, in their own words, the experiences of new graduates as they enter the tech job market – the forces that have driven them to decide whether to stay or leave or, in some cases, leave and return.

With that in mind, Communitech News sat down recently and talked with Carras and several of her classmates about their choices and their rationales. Their views were, in many cases, surprising.

Their opinions and decisions are relevant given they come amid an ongoing global talent crisis: As the world turns progressively more digital and technology based, the demand for graduates with the skills to build society’s new architecture grows. As Silicon Valley investor Marc Andreessen famously wrote in 2011, "Software is eating the world." And the feast has only quickened since then.

In the U.S., in 2018, there were an estimated 200,000 job openings for software developers, a figure expected to rise to one million by 2020. Training institutions can’t keep up.

It’s a similar story here in Waterloo Region. Canadian universities and colleges, and the University of Waterloo in particular, turn out top-flight developers and engineers. But the demand for talent of all kinds can’t be met. Bidding wars and poaching have become common. It’s estimated that Waterloo Region tech firms have 2,000 unfilled jobs at any given time.

“If you have a big name like Google or Microsoft on your resume, it opens a lot of doors for you.”

Meanwhile, U.S. firms with big budgets, big appetites and big, global brand power – which is, the former students say, a big drawing card in itself – are waiting on the doorstep of Canadian graduates, eager to usher them into their own corporate fold, deepening the talent shortage here.

“Prestige [of a big brand] is one of the main reasons [students leave Canada],” says Krishn Ramesh, who, like Carras, graduated from the University of Waterloo in 2018 in Systems Design Engineering. “Pay and prestige. Pay is drastically higher. Prestige, especially early on in your career, is a very valuable signal to future opportunities. If you have a big name like Google or Microsoft on your resume, it opens a lot of doors for you. I don’t think that’s necessarily right, but that’s the reality of it.

“Just like it’s a signal having [University of] Waterloo on your resume.”

Ramesh now works at Microsoft in Seattle and, like Carras, was recruited a full year before he graduated, the offer coming as he completed his last co-op term, also at Microsoft.

Ramesh is also the author of a Medium post last summer titled UWaterloo Systems Design Engineering 2018 Class Profile, which attempted to capture and measure the university experience for that class, the decisions graduates had made post-university and to quantify salary and work outcomes.

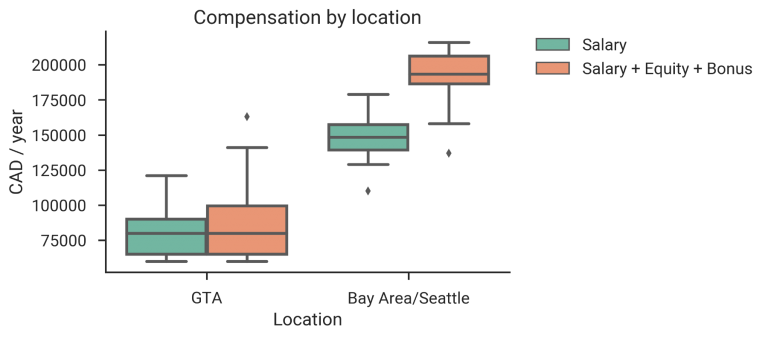

UW Systems Design grad Krishn Ramesh wrote a Medium piece based on data he

gathered from his graduating class, including compensation information. (Graphic

courtesy of Krishn Ramesh/Medium)

There were some interesting findings:

- The median student made CDN$93,000 over six co-op terms and almost half graduated debt-free.

- Co-op compensation in the U.S. was 2.4 times higher than in Canada.

- Bay Area and Seattle compensation post-university (adjusted to Canadian dollars) was 2.4 times higher than in the Toronto-Waterloo Region Corridor; the exchange rate accounted for 1.3 times the difference.

- Big brands – Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Apple and the like – resonate with new grads. So does money and the opportunity to work on big, interesting projects.

- More students chose the Bay Area for their final co-op than any other location, and the progressive gravitation of students away from the Toronto-Waterloo Corridor to the Bay Area or Seattle was pronounced as students advanced through their programs.

The final point, says Carras, is key in terms of understanding how, and why, Canadian students leave Canada. A student’s last co-op term prior to graduation leads, more often than not, to a job offer – an offer that comes months before graduation, meaning a graduate is taken off the market long before they actually take the stage to accept their diploma. By the time Canadian recruiters show up, graduates are often long gone.

“I was speaking to a recruiter [at Palantir] in August, 2017, and I had an offer in front of me by September, 2017 to join the team [for] October, 2018 – so, well in advance of when I would be starting,” says Carras.

“I think the best way that Canadian companies can go about capturing talent early on is being competitive with the cadence at which [U.S. companies] recruit. By the time [Canadian companies] start looking, a significant amount of people have already committed.”

And then there is the money.

Starting salaries for tech workers in the U.S. are much higher than in Canada, reaching north of CDN$200,000; big bonuses and equity plans are common.

The salary disparity isn’t new, and many Canadian tech leaders, including North CEO Stephen Lake (in a 2016 Medium post), have gone to great pains to explain that Canadian salaries are actually competitive once the absurdly high cost of living in California is factored in.

But many recent grads don’t buy it.

“I definitely think you would come out on top, financially speaking, if you go to the States,” says Ramesh.

The cost of living, he acknowledges, is high. But he says new grads are willing to live with roommates and share living space in houses and apartments in order to bring their costs in line. And areas like Denver, Austin and Washington State, where he is based, aren’t nearly as costly as the Bay Area. Factor in the benefits, perks and bonuses, and the U.S., he says, comes out on top by a wide margin.

“Large companies will match your 401K (retirement plan) and healthcare is not a concern because it’s provided by the company, so it’s basically the same as Canada. The extensive benefits big companies offer are sort of unmatched.”

Carol Leaman, CEO at fast-growing Waterloo software company Axonify, understands the U.S. draw, particularly for a graduate at that stage of their life and career.

“I totally get the students’ perspective,” Leaman says. “Who wouldn’t say, when they’re in second or third year, ‘Wow, Amazon is coming at me!’ Then on graduation get a big, fat paycheque. You’re at that time of life where now is the time – see the world, travel. It’s the same with a job. Now is the time to go do that experience before you have a family and you’re tied down. I totally get that.”

And the news that U.S. companies are scouting local talent and snapping it up long before graduation doesn’t surprise her.

“I knew there was a level of aggression happening peripherally; I didn’t realize it was quite to that extent in terms of years in advance but I totally buy it. I think that is, in fact, probably happening left, right and centre.”

“We’re creating an environment here of what it feels like to be in San Francisco, which is not good.”

Of bigger concern for Leaman is what she says is an emerging trend over the past six months – that of well-funded companies like Shopify, Google and Terminal paying U.S.-level salaries to employees here in Canada and in Waterloo Region, skewing the local compensation market and putting pressure on emerging companies.

“We lost a VP who got a 25-per-cent salary bump,” says Leaman. “We lost a VP who got a 30-per-cent salary bump. And we lost a developer who got a 100-per-cent bump.

“We’re creating an environment here of what it feels like to be in San Francisco, which is not good. I can’t take one guy on a team of 40 people, double his pay and then run the risk that other people start sticking their hand up.”

But at the same time that a Shopify is driving up salaries, its emergence signals an important, and potentially positive, development for talent retention, new grads say.

Shopify – a Canadian success story with scale, brand and deep pockets – coupled with the robust presence north of the border of big U.S. companies like Google, Amazon and Microsoft, heralds a maturing of the Canadian scene. Those companies offer the brand and money that gets the attention of new grads, keeping them at home where their salaries feed the economy and tax base.

Helen Tsvirinkal, a 23-year-old UW Systems Design graduate and classmate of Carras and Ramesh, was impressed enough with an offer from Shopify in 2017 to eschew Silicon Valley, accepting a position as a product designer at Shopify’s Toronto office as soon as school was finished. The money was good, she says, and so was the job. And the offer came early, immediately following her final co-op placement, putting her in a position to accept before the big Valley companies came calling.

Helen Tsvirinkal considered working in California but ultimately chose a role with Shopify

in Toronto. Its scale, brand, pay and work rivalled what a U.S. firm could offer.

(Communitech photo: Craig Daniels)

“I did consider going to other companies in California,” says Tsvirinkal, stirring her coffee at a popular downtown Toronto eatery. “I did interview with other companies. It came down to: What are my options, which product am I more excited to work on at the end of the day?

“It ended up that Shopify was the best option for me. In my opinion it’s one of the best options, especially for design.”

Shopify’s scale, brand, pay and the work itself, she says, was on par with what a U.S. firm could offer.

“I see Shopify as that,” she says. “It’s not [quite] the same as Google or Facebook, but I still feel like the experience I’m getting here, and the breadth of knowledge that I’m acquiring, will be beneficial for me no matter what I decide to pursue in the future.

“I don’t think it was a tradeoff to pick Shopify.”

In short, Shopify’s homegrown clout and brand get the attention of graduates.

“If there were more companies like that here, if people felt like it was a valuable place to be for experience and growth, it would be less of a thought that we’re only here for a year or two. I think there would be more opportunity for people to be willing to stay here longer.

“That’s what I’m seeing at Shopify. People love it and there’s almost no reason for them to leave. There’s no downside to working here. You get that competitive pay. It’s also giving people something interesting and challenging to work on – keeps them intrigued year after year.”

“I do think it’s easier to keep people in Waterloo Region now because the ecosystem is what it is – it’s more mature.”

There are signs that other Shopifys are emerging on the not-too-distant horizon. In Waterloo Region alone, several companies are on the cusp of breakouts.

“Over the last 10 years, the proliferation of support systems, the number of companies that have stayed and grown, [has resulted] in more opportunity,” says Leaman. “The funding has changed dramatically, and because there are more of us now recruiting actively, there is a feeling in the community that you do have opportunity that didn’t exist 10 years ago.

“So I do think it’s easier to keep people in Waterloo Region now because the ecosystem is what it is – it’s more mature,” says Leaman. “There’s more opportunity for people to stay and be successful. The landscape of possible employment places has changed dramatically.

“Vidyard, Miovision, Auvik, Magnet Forensics, Clearpath,” she says, listing several mid-size, fast-growing Waterloo Region companies. “Where we’re sort of the same age and stage, we all pay very, very similarly. It’s a very good market rate of pay across the board for all positions.”

The emergence of those very opportunities led Waterloo Region native Alysha Voigt to return home from California last June and accept a position a few months later with Waterloo-based TextNow. Voigt, a 29-year-old UW Software Engineering graduate, had lived in the Bay Area with her Canadian boyfriend since graduation in 2012, working at Microsoft, where she had completed her final co-op.

She flatly admits she was seduced by California’s weather, the job opportunities, the pay and the … vibe.

Alysha Voigt “fell in love” with California, but when the ardour faded, she returned to

Canada. She now works at TextNow in Waterloo. (Communitech photo: Craig Daniels)

“From my perspective, it just felt like California was the place,” recalls Voigt, chatting at TextNow’s new offices in the environmentally-friendly Evolv1 building.

“Everyone talks about it, you hear about Silicon Valley. To me, it was almost this mystical place I had to experience. I just completely fell in love with that area. I’m sure many people do.”

But over time the ardour faded: astronomical rent; rampant social issues; Donald Trump’s arrival as U.S. president, along with an anti-immigrant administration; the long commute to see family and friends. All conspired to push her back home.

The plan, she said, was always to spend a few years in the U.S. and come back. After six years in the Bay Area, with car and apartment leases both coming due, and with her boyfriend’s work visa about to expire, Voigt realized the time had arrived – that if they didn’t act they’d fall prey to circumstances that had ensnared many of their expat Canadian friends, who found partners, settled down, had families, and grew U.S.-based roots, their skills lost to the American market.

“I still had it somewhere in the back of my head that I was going to come back some day. It feels like [Waterloo Region] is, to us, is a better area to want to settle down and actually have a family some day, to buy a house some day and not spend $1 million for a tiny, tiny property. It felt like that even with the winters, it felt better to come back.

“I grew really tired of spending so, so much money on an apartment each month,” she continues. “It was very easy to be spending US$4,000 on a one-bedroom apartment. It was ridiculous. Sure, your salary is higher, too, and that’s very nice, but to me there’s still something about throwing that amount of money away on [rent] that doesn’t sit right. Even though I was making more money, that’s true.

“There’s something visceral about knowingly throwing that much money away every month. And everyone else down there is doing the same thing and not questioning it. Eventually it really gets to you, I think.”

So, too, did the things she witnessed on the streets and in the news. Homelessness. An anti-immigrant sentiment. Gunplay. A winner-take-all ethos that she finally decided wasn’t her.

“I’ll probably look back at that time as one of the best periods of my life. At the same time, I’m still glad that I have moved back.”

“Continuing to live there, it kind of felt like I was implicitly supporting a lot of these horrible things that I’m hearing about every day in the news. Obviously I wasn’t supporting it, but part of me felt like living there for so long, and staying there for so long, was implicitly supporting it.”

Voigt says that neither she nor her boyfriend regret their time in the U.S., but they’re both glad to be home, cold weather and all.

“It was a great experience. I made lots of friends down there, went on tons of great adventures. Great food. Great memories. I’ll probably look back at that time as one of the best periods of my life. At the same time, I’m still glad that I have moved back.”

Family, proximity to the familiar, kept Justin Wong from ever leaving.

Justin Wong took co-op terms outside Canada, but ultimately sought a job closer to

home, at Thomson Reuters in Toronto. (Communitech photo: Craig Daniels)

A member of the UW Systems Design Engineering 2018 class, Wong, like his classmates, tested the tech waters during his co-ops in the Valley and one in Singapore. Unlike many of his classmates, he decided to accept a role closer to home as a software engineer with Thomson Reuters in Toronto.

“It’s been wonderful so far,” he says. “I get to see my parents, my girlfriend and everybody on the weekend and after work and I still get to do what I enjoy doing.

“One of the biggest fears I had [about deciding to stay in Canada] was whether my growth would just stop. Everyone has that fear. What I’ve come to realize is there are tons of opportunities in Toronto and I’m sure in Canada as well. They’re just not as in-your-face.”

The decisions made by Voigt and Wong – to return to Canada in the former’s case, and not to leave in the latter’s – are part of why Devon Galloway believes the talent conundrum facing Canadian tech will successfully sort itself out – that the marketplace of talent will respond to market forces – in this case, the availability of good jobs in a safe, liveable environment. Waterloo Region, he says, has a lot going for it. That belief is largely why Galloway, Chief Technology Officer at Kitchener-based startup Vidyard, and co-founder Michael Litt, made a bet on Waterloo Region when they formed their company in 2010, deciding to remain in Canada after exiting the Valley’s vaunted YCombinator accelerator.

“I pretty firmly believe that the market is just operating efficiently,” says Galloway.

It’s also his opinion that the demand for talent in Waterloo Region, which he acknowledges is real and pronounced, has not begun to approach the scale of the problem facing Silicon Valley. As a result, incomes here are lower. Demand not as frenzied.

“I just haven’t found we have the level of a dogfight in our market that firms in Silicon Valley are facing,” he says.

“Silicon Valley has the world’s biggest talent war by a longshot. If those companies are not recruiting a year in advance, they’re unable to get anybody. Companies in Waterloo haven’t yet had to do that. The talent hunt is just not that crazy. The market is not equal to Silicon Valley.”

As a result, he isn’t yet concerned about competing for the talent that opts to head west.

“I have first-hand knowledge of a new grad from Queen’s, a computer science grad, who has a job offer to go to a firm in the Valley at $160,000 US. If that’s the lifestyle and the type of company they want to work at, and the economics and lifestyle works for them, they should take that offer.

“If dollars are the only thing that moves the market, then you have to compete on dollars. While we are very competitive with our salary numbers and, I think, very fair, our numbers are based on what the market is telling us.

“That new grad from Queen’s computer science is, quite frankly, not worth $160,000 to me. While they may be a great candidate and a great person, my market is different, so I behave differently – in fairness to all the people we have and [the ones] we’re [currently] recruiting.”

“I think it’s a mistake of new grads to equate firm size to impact.”

Galloway, like Leaman, says he understands how a new graduate would be seduced by the siren song of the Valley and the draw of big firms with big brand power.

But he is firm in believing that new graduates risk shortchanging their careers by signing on with them directly out of school because they risk becoming lost in the sprawl of a big organization, spending years without shipping so much as a single line of code.

“I think it’s a mistake of new grads to equate firm size to impact,” he said. “Certainly the brand is good on the resume.

“But I’ll tell you, when we’re interviewing, I spend the vast majority of my time talking to candidates about the projects they accomplished and their specific role in the project. When you come to a firm of Vidyard’s size, or especially, a 50-person firm, you work there for a year and you can name numerous projects that you’ve led or had very significant roles in.

“You can go work at Google for a year and come out and say, ‘I’ve done nothing. An actual project that I’ve completed and shipped to production? I don’t have one to talk about.’

“And the brand [of a big company like Google] is very good. I won’t debate that. But when we get into the substance of the interview, we do talk in depth about specific projects you accomplished. What did you do? I would dare to bet that at Vidyard you will have many more things to say than a Google employee after a year or two years. If you alternatively go to a two-person startup, you will have many more things to say you accomplished there than at Vidyard.”

Galloway acknowledges that a big company has many “incredibly talented, incredibly senior engineers” who can teach a new grad “so many amazing things.

“But you don’t necessarily get to work on a project with them,” says Galloway. “You don’t actually get fingers to keyboard, to write some code, and do something.”

“Every candidate is different and has different motivations. For people who strive for the brand, Google is fantastic. For people who strive for breadth of experience and incredible opportunity to touch and feel stuff, the two-person startup is incredible.

“I think [Vidyard is] in this interesting sweet spot. You can ship code to production your first week, but you can also learn from talented 20-year, 10-year engineers with a lot of knowledge to share.

“My dad once used this line with me and I’ve used it with many candidates since: ‘At this point in your career, fresh out of school, is it the time to learn or the time to earn?’

“That line has stuck with me forever.”

Alex Kolicich, a 2008 Waterloo grad, says recruiting top talent costs more but ultimately

brings outsized productivity gains to those companies willing to shell out.

(Communitech photo: Anthony Reinhart

Alex Kolicich is a Canadian expat and founding partner of San Francisco-based venture capital firm 8VC, whose roster of advisors includes A-list tech veterans, Hollywood celebrities and former prime minister Stephen Harper.

Kolicich grew up in Hamilton and graduated in 2008 from University of Waterloo with a B.Sc. in Software Engineering. He finished in the top 10 per cent of his class and, unsurprisingly, was recruited hard by Google, Microsoft, Apple – “Every major company out there,” he says.

What surprised him was the company he never heard from – Waterloo’s Research In Motion (RIM), now known as BlackBerry, and at the time Canada’s largest and most important tech firm, with global cachet.

“I’m like, if they’re not talking to me, who are they talking to? It just didn’t make any sense.”

Given RIM’s local pedigree, Kolicich didn’t want to dismiss the company out of hand. He asked around of acquaintances who had taken jobs there. It turned out they were making half of what Google had offered him.

“I thought, this is backwards. They don’t know what game they’re playing.”

The game, in Kolicich’s opinion, is a Darwinian competition to survive and thrive in the global marketplace, and a company that wants to be the best in the world has to pay accordingly. Canadian firms, he says, have a habit of paying less than world market scale and then touting their cost advantage – an advantage, he says, that’s ephemeral.

“Everyone talks about cost [in Canada]: ‘Oh, look, we have lower salaries up here.’

“But the counterpoint I always say to people is, ‘What technology company that you respect competes on the cost of their engineers?’

“Google pays the highest. Apple doesn’t pay the highest, but they pay very high relative to the market. Amazon pays very high. Microsoft pays very high.

“When [Toronto-Waterloo Corridor firms] say, ‘Hey, we pay what’s best in Toronto.’ I say, ‘Are you competing to be the best company in Toronto or the best company in the world?’”

The answer is always the latter. His rejoinder?

“So why are you not hiring people that you think are the best in the world, then?”

Mystified by RIM’s hiring processes and salaries, Kolicich went on to take the offer from Google and move out to the Valley; he’s since touched down in various tech roles, including working with mega-entrepreneur and Palantir founder Peter Thiel, as a principal at Mithril Capital Management. At 8VC, he keeps a close eye on the Canadian tech scene.

Some Canadian companies, like Shopify and North (formerly Thalmic Labs), “now do an excellent job and are very aggressive about recruiting people,” he says.

But others, not.

“Part of it, honestly, is an environment thing, where it’s easier to recruit in Canada, so I feel like people get complacent. Whereas down here it’s hard, so [companies] get very, very good at recruiting. So much so, that it’s their first order of concern: ‘We need to get the best people.’

“So I think there are cultural differences that have evolved. I don’t think it’s ‘being Canadian’ and not being aggressive, because there are plenty of aggressive Canadians. Down here, it’s literally war. If you’re practising at war, you get good at fighting.”

And, he says, big, successful tech companies have come to understand that the best talent not only costs more, but it pays back in a big way. The best engineers cost more, but they get more done – sometimes, orders of magnitude more – something he says Canadian firms largely don’t yet accept.

“Down here, the reputation of [University of] Waterloo is probably better than it is in Waterloo.”

“[Software engineering] is one of those rare disciplines, and it’s unintuitive to business people in particular,” he says. In traditional engineering, “you build a bridge, you hire another person and another person is not going to build that bridge 10 times faster. That’s not the way it works.

“But in [software] engineering there are people who literally are 10 times better. So if you pay them 50 per cent or 100 per cent [more], you’re actually still doing well from a productivity perspective.

“That’s what the majors, I think, have realized. Paying up has its advantages and does pay off in terms of productivity.”

Productivity, he says, is why recruiters target University of Waterloo’s graduates. UW, he says, has an outsized reputation in the Bay Area. “I think, in technology in particular down here, the reputation of [University of] Waterloo is probably better than it is in Waterloo. You’ll hear Waterloo talked about in terms like MIT, Harvard, Stanford. That’s literally how people think about it down here. People love [their] graduates.

“[They] hit the ground running and are incredibly productive, which kind of blows people’s minds. You’re not like a typical new grad. I think the [kind] of person is very good, as well. [They’re] very focused on just getting things done. There’s not a lot of ego; [it’s an] incredibly, incredibly highly coveted place to recruit from, and always on people’s top five.”

The inference being, Waterloo grads are worth more. And Canadian firms should take note.

“So then, when [a U.S. company goes] to Canada, where it’s a little less competitive, relatively speaking, then you’re way more aggressive than people there, and you’re going to scoop up all the top talent before they even know what happened.”

Sara McKenzie quickly admits she’s not a typical University of Waterloo engineering graduate. She doesn’t consider herself a “techie” in the usual sense of the word, despite the fact she’s a member of the 2018 class in Systems Design Engineering. “I’m not a technical person by engineering standards,” she says, talking over coffee at the Communitech Hub.

Unlike many of her classmates, McKenzie, 23, didn’t go to the Valley after graduation. And neither did she accept a job at a local tech firm. Instead, she took off for South America and travelled.

She considers herself environmentally minded. Humanitarian minded. Her strengths, she says, are “raw determination” and that she has a mind for logistics.

And she’s fiercely independent – a person determined to chart her own path and carve out life on her own terms. The professional life she sees for herself is as an independent consultant, and it’s a role she currently holds at Communitech, willing to trade lack of security for freedom.

“I’ve never done well fitting in a rigid structure,” she says.

Unsurprisingly, all that told, she looks at her graduating class through something of a detached observer’s lens – simultaneously one of them and not one of them.

“Everyone feels like, coming out of university, you’re a small fish in a massive pond,” she says. “And so they want to do anything they possibly can to differentiate themselves.”

Her peers, she believes, want to make a difference, to stand out. They want to do so in an ethical fashion. They want a clean planet. They want a good job, and decent pay. They want to work on big, important problems. And they want to do so for companies that don’t harm others or the environment as a byproduct of their business.

In short, cool matters, and they get to define what “cool” means.

“The cooler your product and your company,” the better chance a company has of finding new talent, she says, adding that today’s new-grad job checklist includes:

“The reputation within the tech world. Is it an innovative company? Do they have cool practices?

“There are lots of corporate giants in the corporate innovation area that aren’t cool enough for people to work at,” she says. “They’re too big, they [have] too much red tape, they still have legacy processes in place. Even if they are now cool and innovate, their name still carries that old reputation.”

And old ways, old assumptions, she says, don’t cut it anymore. The message appears to be that companies, including the ones here, need to step up their game. Pay more. Recruit more aggressively.

Because in the global chase for tech talent, the talent has the upper hand. Today’s grads are smart. They’re in demand. They want it all.

They just might get it.