Talent is the No. 1 challenge for tech leaders, and the competition for the best people is global. In this four-part series, Tech News takes a deep dive into Canada's talent crunch, talking with more than a dozen founders, recruiters, front-line workers and industry observers. This is Part 2.

After touring 18 tech hubs around the world, Dan Herman returned to Toronto recently with plenty of insights. One stood out above the rest: In the competition for tech talent, Canada is up against a whole new field of fiercely determined players.

“The story now is that it’s not just us and it’s not just San Francisco who’s competing for talent,” says Herman, an industry observer who is producing a television series called Magnetic Cities. “There are dozens of cities around the world, both established and up and coming, that are desperately vying to get people to come to their shores. And that puts Canada’s challenge into perspective: What’s our value proposition to attract global talent today?”

It’s a question in desperate need of an answer.

Talent is the No. 1 challenge for tech leaders everywhere. Software developers, hardware engineers, product managers, cybersecurity specialists, data experts and experienced executives are all red-hot commodities right around the planet.

The challenge has always existed, but the pandemic has juiced it with rocket fuel –increasing the demand for tech products, accelerating remote work and prompting cash-rich investors to fund technology companies like never before.

According to a recent report by the Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC), at least 55 per cent of Canadian tech entrepreneurs are “struggling to hire the employees they need.”

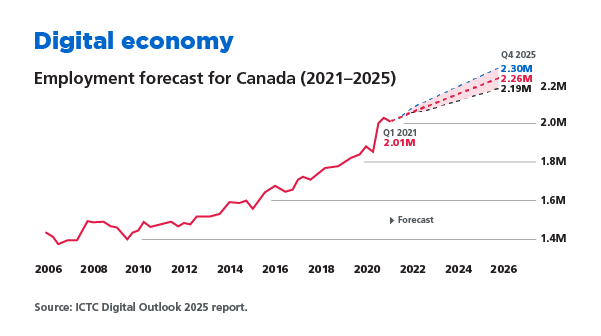

The Canadian economy alone will need to fill 250,000 tech jobs over the next three years, according to the Information and Communications Technology Council.

(Communitech graphic: Grace Stallard)

And the demand goes beyond developers and programmers. Fast-growing companies are looking for experienced leaders who know how to build teams and enter new markets, says Kristina McDougall, founder and Managing Partner at Waterloo-based executive search firm Artemis Canada.

“It’s that scaling experience that is absolutely in demand,” she says. “The most common ask – and there’s not a big enough pool of these candidates to go around – is ‘find me someone who’s seen this journey before, find me someone who has taken a sales organization from $10 million in recurring revenue to $100 million in recurring revenue... find us someone who’s taken an engineering team from 20 to 100 people, or find someone who’s scaled customers from 50 customers to 1,000 customers.’”

The stakes are high for individual companies and for the national economy.

“If Canada cannot get ahead of the sector’s immediate shortage and demonstrate that it has ‘talent ready and waiting,’ the country will risk being left behind in the race to grow the sector’s economic base, keep companies here and attract new ones,” Sheldon Levy, a veteran university administrator and policy adviser, wrote in a recent opinion piece in the Globe and Mail.

On one level, the issue boils down to a basic axiom: the key to hiring talent in a competitive market is to become more competitive.

“Every jurisdiction in the world has shortages of talent in any (sector) that’s growing... that's just the way the market works,” says Charles Plant, a tech entrepreneur and researcher who studies rapid-growth companies.

“Being competitive and getting talent is what Google does,” he adds by way of example. “They are out actively recruiting, they are paying top-notch dollars and giving people interesting things to do. If you can do that, you’re not going to have a shortage.”

Many agree but say governments also have a role to play through immigration policy, tax incentives, skills training and other forms of public support.

“It is clear that Canadian companies must offer competitive wages and incentives to compete in this new labour market,” the Council of Canadian Innovators (CCI) says in its recently released Talent and Skills Strategy. “However, there is a significant onus on policymakers who must adapt their thinking to reflect the needs of the 21st century economy.”

The CCI document offers 13 recommendations aimed at federal and provincial governments. The proposals are organized into four categories: co-ordination of efforts and capacity building; talent attraction; talent generation; and talent retention.

Several recommendations are aimed at immigration policy. The central theme is to make it easier and faster for people with the most in-demand skills to come to Canada and work in tech.

One CCI proposal – the creation of a “high-potential visa” – is similar to a UK program that allows the most in-demand professionals to enter or remain in the country without a job offer in hand. Another idea – aimed at “digital nomads” – urges Canada to find ways to entice the growing number of highly mobile skilled tech workers to relocate to Canadian soil, for short or longer periods.

Whatever the details, Dan Herman says Canada can no longer rely on “yesterday’s brand.” The country needs to develop a new marketing pitch to foreign tech workers that’s based on the new realities of talent competition.

Those realities include remote work and improved internet access, both of which allow international tech talent to find success in their home countries. Another reality, as Canadian founders have experienced themselves recently, is the relative ease with which investment capital flows across international borders.

Herman says he was “blown away” by the thriving tech communities he encountered in places such as Nairobi, Kenya and Santiago, Chile.

In Senegal, he met the founder of a 50-person logistics company who had spent time working in Montreal.

What's our value proposition to global talent today? What's our value proposition to our own talent to stay?"

– Dan Herman

“I asked him at one point, ‘Why didn’t you stay in Montreal to build this?’ And he said, ‘Well, I could have stayed in Montreal and dealt with the winter and the housing crisis, or I could come here where I’ve got greenfield opportunity, I’ve got amazing talent and it’s home.”

So, what’s the takeaway?

Canada needs to see the world through the eyes of prospective tech immigrants and update our talent pitch.

“What’s our value proposition to global talent today? What’s our value proposition to our own talent to stay?’’ says Herman, who earned a business degree at Wilfrid Laurier University, a master’s degree from the London School of Economics and a PhD from the Balsillie School of International Affairs in Waterloo. “I don’t think we have a clarified and updated contemporary view of what the pitch is to come to Canada, but we need one.”

Herman also argues that Canadian businesses need to be more aggressive in their international recruiting efforts.

“It’s not enough to offer (international candidates) a big salary and hope they’ll come here because, as nice as this is to me, for a lot of people (Canada) is still really cold and unappealing,” he says. “If you want the talent, you’ve got to knock on their door at home and say, ‘You can stay here but work for me and build something awesome.’”

The role of innovation is another issue that comes up in talent discussions, especially regarding how to attract the best of the best.

There’s a school of thought that Canadian businesses do poorly at innovation, due in part to years of chronic underspending on R&D. One of the fallout effects, the theory goes, is that we have trouble attracting and retaining the kind of top talent that’s drawn to work on cutting-edge technology.

“(There’s a) ‘low-innovation equilibrium’ where you can’t compete for top talent because the kind of work that can attract top talent isn’t happening, and that creates a self-reinforcing cycle,” explains Viet Vu, Senior Economist at the Brookfield Institute for Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Toronto.

While paying top wages to top talent will help, Vu says higher R&D spending and a focus on innovation should be part of any talent strategy.

“We want our economy to be innovative, we want companies that are not just adopting the latest technology but to create new technologies that supplant what’s existing, and that doesn’t seem to be happening as often as it should right now, and it hasn’t been for a long time,” he says.

Others have a different take.

Charles Plant says the focus on technological innovation often ignores the importance of business-model innovation.

Charles Plant, an innovation economist, seen here at Communitech in 2020.

(Communitech photo: Alex Kinsella)

The success of companies such as Salesforce, Airbnb and Uber has more to do with innovative business models than leading-edge technology, he says.

“Their software is not particularly innovative… but there are plenty of people that would love to work at companies like that.”

The fixation with technological innovation also diverts attention away from the importance of sales and marketing, Plant says.

“In the software field, successful companies spend twice as much on marketing and sales as they do on R&D. What drives success? It’s getting out to the market, it’s not having a better widget.”

Herman argues that Canada creates lots of innovative technology, especially through university research. The challenge we have is commercializing and retaining ownership of those brilliant ideas.

“What you see is a challenge to take those transformational ideas and turn them into big companies,” says Herman, who also serves as a special adviser to the government of Ontario on intellectual property. “What we need to do is transfer that (IP) into the hands of domestic firms, because then the connection between that researcher who’s working on what’s groundbreaking and the company that’s going to build prosperity here, the closer we can keep that here, the more you actually break that cycle.”

The other link between post-secondary institutions and industry is the role of education in creating more tech talent.

A recent “talent pipeline” report by University Canada West (UCW) in Vancouver focuses on British Columbia, but the message could apply to post-secondary institutions across the country.

“Universities share a collective responsibility to understand what industry needs to help the economy grow, and as importantly, to prepare students to meet those needs,” says Sheldon Levy, UCW’s Interim President. “As we reimagine the post-COVID economy, we must work together with industry to better prepare the tech workforce of the future.”

Perhaps the overall talent challenge facing Canada is best summed up by the Council of Canadian Innovators.

“There is no simple solution to this issue, but the goal for Canadian governments should not be complicated,” the CCI talent report says. “To ensure Canadian-headquartered technology companies are able to succeed in this emerging and expansive labour market, governments must increase the pool of highly skilled talent in Canada and ensure that a range of policies are introduced to make it easier for companies to attract, retain and generate the best and brightest workers.”

Second in a four-part series.

Part 1: How Canadian tech founders are running flat-out to fill roles

Part 3: Employees share what's important to them in a job

Part 4: 'Boomerang' tech workers on why they came home to Canada