They call it the “SOC” – pronounced “sock,” and shorthand for security operations centre. It is a room the size of a school gymnasium that harbours the kind of silent, efficient tension you might find in a busy air traffic control centre.

On this day, weeks before COVID-19 would lay the world low, it is sealed off, not only from the grey winter skies but from the rest of the company to which it belongs, save for the internet pipe that feeds its computers. SOC analysts, 15 to 20 of them depending on the day, are at work stations, quietly monitoring their screens.

Every 47 seconds, a threat – sometimes overt, sometimes cloaked in a disguise of ones and zeros – emerges from the pipe. It is shepherded into the room and welcomed by the operators on duty the way a martial artist would welcome an opponent to the mat or, perhaps more fittingly, the way a spider might welcome a fly.

The eSentire secuirty operation centre (SOC)

(Photo courtesy of eSentire)

Computer code, generated by malicious, unseen hands perhaps half a world away, enters, probes for weakness, and is then neutered, smothered by an operator’s counter-measures or by those of a team of operators, if necessary. They render the threat inert in the way a sapper might defuse an explosive.

And then the cycle begins anew. Another threat. Another solution. Every 47 seconds, on average, 24/7, 365.

This is a typical pre-pandemic day at Waterloo’s eSentire, a 450-person company that is one of 40-odd firms in Waterloo Region that specialize in some form of cybersecurity – protecting computers, networks, intellectual property, identity, fortunes and, in some cases, even lives.

Risk assessment. Threat detection. Embedded security. Cryptography.

Waterloo Region has become, in the estimation of Don Bowman, former chief technology officer at network optimization company Sandvine and founder and CEO of a cloud-based cybersecurity startup called Agilicus, the fourth-most important cybersecurity cluster in the world after Israel, Silicon Valley and Boston. It punches far above its weight given the size of the community that supports it. But why? How? Why here?

For an answer you have to travel back in time and over an ocean, back to January 1941 and wartime Britain, when a young University of Cambridge research mathematician by the name of William Thomas Tutte was invited to an interview by a group of secret codebreakers and eventually asked to help the British government save the world from Nazi tyranny.

Tutte had no way to know how crucially important, and how ultra-secret, the role he was to play in the war would become. And Tutte certainly wouldn’t have guessed that, many years later, he would walk the halls of a new university built on farmland in Waterloo, Ontario, carrying that secret in his head, leveraging its mathematical power, while simultaneously gathering to him the people and expertise that would become ground zero for the region’s cybersecurity industry.

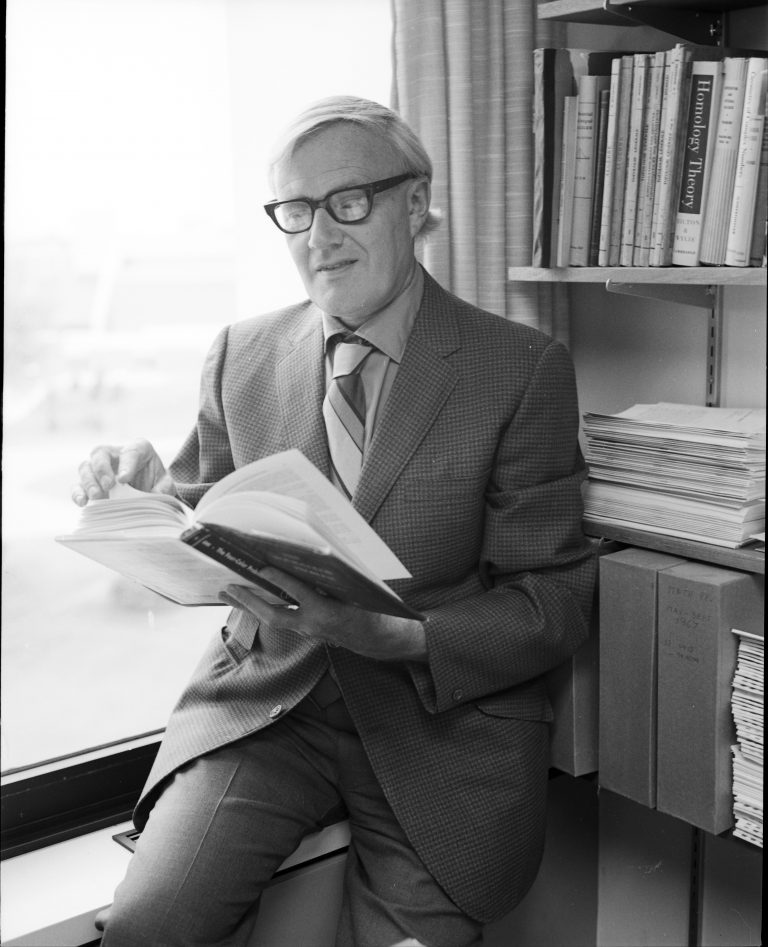

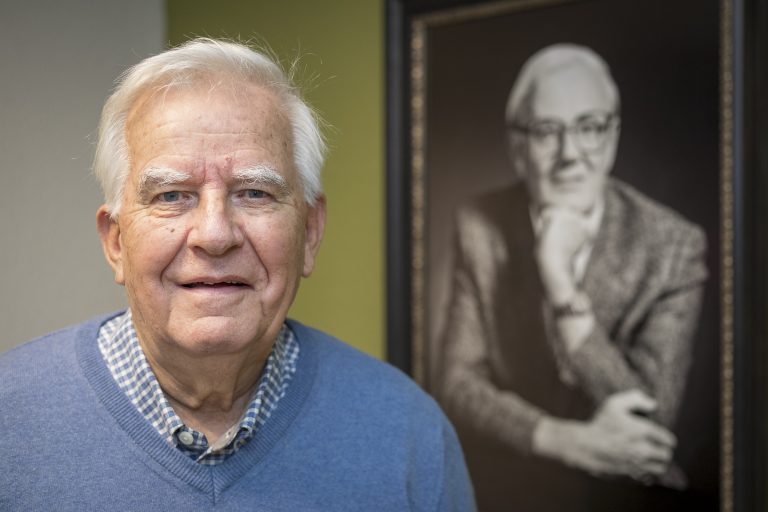

Dan Younger is silver-haired, 84, and mostly retired. Until the COVID-19 pandemic struck, he maintained an office on the fifth floor of the University of Waterloo’s MC building – mathematics and computers – where he is listed as “adjunct professor.” He has had a long, distinguished teaching and research career specializing in graph theory, which is tied to the geometric properties of a field of mathematics called combinatorics and optimization.

The roots of C&O, as it’s colloquially known, date back 3,700 years, but the field gained in relevance and importance with the emergence of digital computers.

Younger, who studied electrical engineering as an undergraduate at Columbia University in New York, first encountered Bill Tutte in the flesh in 1963 (the same year Younger received his PhD), at a lecture Tutte delivered at Princeton called, “How to draw a graph.” The lecture would become famous.

Graph theory was Younger’s main interest, and Tutte, he says, “was its most famous proponent,” gaining renown, along with three other Cambridge undergraduates, for a paper published in 1940 that described a solution, and the solution’s theory, behind a math problem called “squaring the square.” Younger was interested in squaring the square because he was an electrical engineer, and the solution Tutte described relied on a link with the mathematics of electrical circuits.

Squaring the square was a problem previously deemed unsolvable. And yet here it was, solved. Tutte helped not only solve it, but explain it. Unsurprisingly, the paper caught the eye of cryptographers working at Bletchley Park, Britain’s then-ultra-secret, and now famous, code-breaking facility, established not long after Britain declared war on Nazi Germany in 1939.

In April of 1941, at age 23, Tutte went to work at Bletchley, joining other mathematicians such as Alan Turing, whose life and war exploits were featured in the popular 2014 Hollywood film The Imitation Game.

The Bletchley Park Mansion, where 23-year-old Bill Tutte initially worked on the

ground floor, in the Research Section. (Photo: Claire Butterfield)

By the time Tutte arrived, Turing was hard at work on a code, also now famous, called Enigma. Cracking Enigma’s decrypts was vital to the British war effort because it was used by the German navy, whose U-boats early in the war threatened the control of Atlantic sea lanes and were slowly starving Britain of the means to wage battle.

But there was another German code, one far less known today and at least as important as Enigma, known as Fish. Referred to by the British as “Tunny” (British usage for tuna), Fish was more complex than Enigma and far less was known about the machine that produced it. It was employed by the German army, as opposed to the navy, and was relied upon by Hitler and his generals for high-level communication between Berlin and commanders in the field. “Tunny” had so far bedevilled British attempts to crack it.

But in August of 1941, a bit of fortune – and Tutte – intervened. What happened next was, in Younger’s opinion, “incredible, just incredible.”

A Fish-encoded message of 4,000 characters was sent to Berlin by a German army teleprinter in Athens. The message was not properly received and so it was sent again – but with the identical code settings, a violation of the Germans’ usual coding and security protocols. Moreover, and crucially, the operator who retyped the message made several small punctuation changes while preparing the second transmission.

Those changes proved to be the clues that a Bletchley codebreaker by the name of John Tiltman needed to reproduce the string of 4,000 characters as they emerged from the coding machine. But what to do with them?

They were handed to Tutte who, in October of 1941, began to methodically piece together what he believed to be the structure of the machine that created the message.

Over four months, Tutte deduced that the machine, which later became known as the Lorenz, had 12 wheels instead of the Enigma’s three. He determined that the 12 wheels were arranged in two groups of five, with two additional wheels serving an executive function over all the others, and that the first wheel must have 41 spokes, and the second, 43. And so on.

The Lorenz coding machine. (Photo: Claire Butterfield)

Tutte, in other words, recreated the machine without ever having seen it.

To appreciate the magnitude of the achievement, consider that when Turing was working on cracking Enigma, he and his team had one of the actual Enigma machines on site to work with.

Tutte didn’t. So he reinvented it, using math.

“In effect, they recreated the Lorenz machine, as real as if it were physically there,” wrote Younger in a 2012 paper.

Tony Sale, an engineer who worked with MI5, the British secret service, has called Tutte’s accomplishment simply “the greatest intellectual feat of the entire war.”

But Tutte didn’t stop there.

He then created an algorithm called the “Statistical Method,” that would, using the enciphered Tunny messages, reveal the exact settings of the Lorenz machine’s wheels, which would, in turn, allow the messages to be read.

The algorithm, however, needed help. The Lorenz machine’s wheels could be arranged in 16 billion billion (or 16 quintillion – that’s 16 followed by 18 zeros) different settings, meaning the algorithm would need to test an enormous number of possible solutions, far more work than an army of humans could reasonably perform in the urgent time required.

For that, Tutte needed a machine of his own.

A Replica of COLOSSUS, the computer built by the British Post Office that enabled

Bletchley Park codebreakers to decipher the Fish code produced by the Lorenz

machine. (Photo by Mike McBey, Flickr, licensed under CC BY 2.

In 1943, the British Post Office designed and created just that, the world’s first programmable computer, a 1,700-vacuum-tube monster that was appropriately called COLOSSUS (COLOSSUS, as an aside, was different from the machine known as “the Bombe” that Turing used to break Enigma).

And from that point forward, the British were able to read Fish.

“Tunny decrypts contributed to the defeat of Germany at the Battle of Kursk in the summer of 1943 and to all subsequent campaigns, including the D-Day invasions,” says Younger. “It shortened the war.”

So. Tutte cracked a more difficult code, with access to far less information, than Enigma. But there were no books about his feat. No movies. No citation of thanks from 10 Downing Street – not, at least, until 2012, when a letter was sent, after Tutte’s death, to his family. Because for decades, not even after the story of Enigma emerged, did anyone outside of Bletchley Park know.

"I was the bait."

Ron Mullin, a retired University of Waterloo mathematician and cryptographer, is sitting in the living room of the Kitchener home he shares with his wife Janet, taking a break from packing for a mid-winter car trip to Florida, and describing the arc of his career.

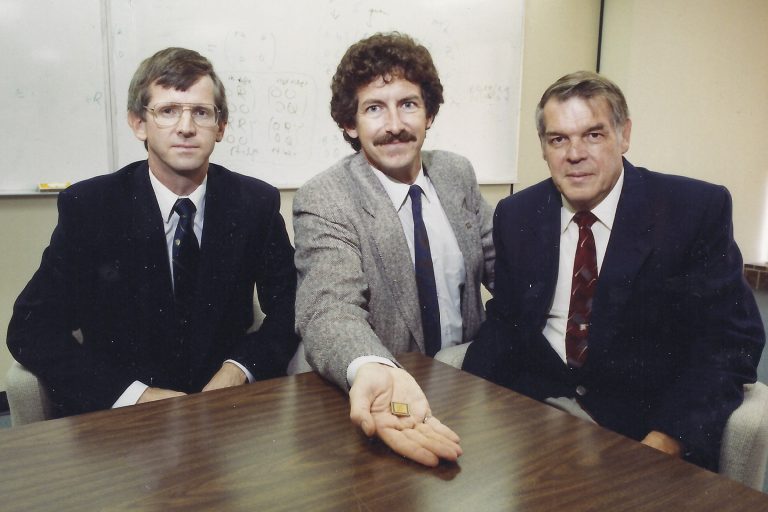

Mullin, now 84, has the distinction of being the first-ever UW graduate, receiving an MA in mathematics in 1960. He also has the distinction of being one of the co-founders, in 1985, of an encryption company called Certicom, which would eventually be bought out by a smartphone maker called Research In Motion (RIM), in 2009, to bolster the security of RIM’s BlackBerry devices. But we’re getting ahead of the story.

In 1959, Ron Mullin was a promising young math and cryptology graduate student at Western University, or University of Western Ontario as it was known then. He had been offered money – “$5,000 or $6,000, a lot of money in those days for a student” – to come and lecture at University of Waterloo while he finished up his graduate work.

University of Waterloo, founded in 1957, was only a couple of years old then, a collection of buildings erected on muddy farmland on the then-fringe of the city.

The head of UW’s math department, Ralph Stanton, was eager to build the fledgling school’s mathematics bonafides. Not only was Stanton a suitor of Mullin’s brainpower, he reasoned that if Tutte – who in Stanton’s opinion was an underappreciated mathematics superstar – were given the opportunity to mentor a bright, eager, cryptography grad student like Mullin, it might help convince Tutte to move to UW and build its combinatorics and optimization capabilities.

Tutte by that time was teaching at the University of Toronto, where he had moved in 1948, not long after the end of the war, unable to find a teaching position in post-war Great Britain.

At U of T, Tutte “was just sort of an adjunct,” says Younger, “on the faculty of a department which was basically interested in algebra and classical mathematics. And so he was never promoted or never taught courses that were, shall we say, in his wheelhouse.”

University of Waterloo, on the other hand, was new, willing to experiment, to take risks – co-op style education being one of those experiments.

“And so I think that that’s one reason that attracted [Tutte] to the idea of coming to Waterloo – the promise, or the idea, that he would be able to teach what he wanted here,” says Younger.

And what Tutte wanted to teach was combinatorics and optimization mathematics – a field crucial not only to cryptography, but to Waterloo’s other emerging speciality: computer science.

Bill Tutte in 1968, near his home in West Montrose, Ont., near Waterloo.

(Photo courtesy of the Youlden family)

So, in 1962, Tutte came.

Mullin, in 1964, would complete his PhD under Tutte and in 1967 become a founding member of Waterloo’s new Department of Combinatorics and Optimization. That same year, Younger was hired and became the managing editor of “the most famous journal of combinatorial mathematics,” the Journal of Combinatorial Theory, of which Tutte was the overall editor.

As Waterloo’s C&O reputation grew, other PhD students came to Waterloo to study under Tutte: Arthur Hobbs, Neil Robertson, Ken Berman, Richard Steinberg, Will Brown, John Wilson and Stephene Foldes.

“Combinatorics didn’t have a home in other universities,” says Younger. Once Tutte arrived at Waterloo, combinatorics “became kind of a permanent seminar here, where people would come from all over the world and stay either for six months, or people like myself came and stayed. I mean, it was an incredible period and Waterloo soon became a very famous place.”

Bill Tutte at the University of Waterloo.

(Photo courtesy of University of Waterloo)

But no one at Waterloo, or anywhere else, knew about Tutte’s wartime past. Younger and Tutte, in fact, would go on hikes together along the rivers and tributaries of the Grand River watershed and Tutte, says Younger, would talk about “flowers and astronomy.” Never a word about the war.

But in May of 1997 – more than two decades after details of Enigma had emerged and four days before Tutte’s 80th birthday – that all changed with an article that appeared in the magazine New Scientist. The story was about COLOSSUS, quoting former MI5 engineer Tony Sale, who was interested in rebuilding the computer in order to preserve the wartime achievements of Bletchley.

When the U.S. National Security Agency in 1996 declassified a bundle of documents about Bletchley that referenced COLOSSUS, Sale was free to tell all. Tutte’s role, for the first time, was revealed, and in considerable detail.

As you might imagine, the revelations reverberated along the University of Waterloo’s hallways.

“It was overwhelming to realize what he had done,” says Mullin. “I mean, how many lives did he save?”

For Younger, the news connected “a lot of dots, [but] it took a while before one could grasp just how significant the role was that Tutte actually played.”

But grasp it they did. In 2001, a year before his death, Tutte was presented with the Order of Canada by then-governor general Adrienne Clarkson. The citation specifically referenced Tutte’s wartime contribution, something Younger says mattered to Tutte a great deal after harbouring his secret for so many decades.

“The fact that a government – it wasn’t the British government perhaps, but a government – gave him that recognition was very important to him,” Younger says.

Looking back today, Younger can plainly see the influence the war had on Tutte’s work at Waterloo. Tutte had an affinity, for example, for formulas that were “always practical” rather than theoretical, and practicality was something one of Tutte’s students, Ron Mullin, would parlay into a company that redefined encryption.

Dan Younger stands near a portrait of Bill Tutte in the fifth-floor hallway of the

University of Waterloo’s Math and Computer Building.

(Communitech photo: Anthony Reinhart)

When Barack Obama ascended to the White House in 2008, he famously refused to turn in his BlackBerry device. The night sweats his decision induced among U.S. security personnel were eased by the fact his device employed a type of security, licensed by the National Security Agency for government communications, called Elliptic Curve Cryptography, or ECC.

Elliptic Curve Cryptography was the signature product of a Waterloo company called Certicom, and the technology was so foundational to the security of RIM’s devices that RIM acquired Certicom in a hostile takeover in 2009.

Certicom was founded by Ron Mullin and fellow UW math profs Gord Agnew and Scott Vanstone in 1985, roughly a year after Waterloo student Mike Lazaridis and his friend Doug Fregin founded RIM, the maker of Obama’s device.

(Left to right) Certicom co-founders Scott Vanstone, Gord Agnew and Ron Mullin, 1987.

(Photo courtesy of University of Waterloo)

The genius of ECC is that it speeds up the encryption process, generating shorter encryption keys without loss of security. And that security played an enormous role in the global adoption of RIM’s devices and the ultimate accelerated growth of the company among the companies and businesses that were its main customers.

“I think [a mindset of security at RIM] got started because of Mike Lazaridis and his vision,” says Mike Morrissey, Senior Vice-President of Research and Development at Arctic Wolf Networks.

Arctic Wolf, like eSentire, is a cybersecurity company that exists to protect the networks of other companies. Launched in 2012 and co-founded by University of Waterloo graduate Kim Tremblay, it was recently valued at US$1.3 billion and announced plans to move its headquarters to Minnesota from California. Arctic Wolf has a large and growing presence in north Waterloo, housed in the same sprawling complex as eSentire, a building which additionally houses software security giant McAfee and scale-up Auvik Networks.

Morrissey spent more than seven years at RIM (later to be known simply as BlackBerry), most of them at the vice-president level, and was responsible for Certicom.

Morrissey traces the emergence of the region and its mindset of security back to Mike Lazaridis “and the talent level and drive of the people that were collected at that time at BlackBerry.”

So, let’s pause now and follow the cyber trail so far: from Bill Tutte, to University of Waterloo, to Ron Mullin, to Certicom, to BlackBerry. And then the trail quickly branches in many directions.

Because then, in a virtuous irony, came the eventual decline of BlackBerry’s handset business, and the thousands of layoffs that occurred between 2011 and 2015, layoffs which would help fuel the growth of Waterloo Region as a cyber cluster.

As people at BlackBerry were let go or changed roles, they carried their cybersecurity mindset and knowledge with them, spawning companies, training people, generating ideas.

- Lazaridis and Fregin would pivot to the development of quantum computing.

- Scott Totzke, BlackBerry’s former senior vice-president of security, would go on to become CEO at ISARA, a company he co-founded to secure the world’s data from the threat posed by the development of quantum computers. His company has been funded, in part, by the Lazaridis- and Fregin-led Quantum Valley Investments.

- After RIM acquired Certicom, Certicom co-founder Scott Vanstone and his wife Sherry Shannon-Vanstone, a cryptologic mathematician, founded TrustPoint, which secures Internet of Things devices; TrustPoint was acquired in 2017 by ETAS Embedded Systems, a division of the giant Bosch Group of companies.

- Former BlackBerry vice-president Adam Belsher teamed up with ex-police officer Jad Saliba and became CEO at Waterloo’s Magnet Forensics.

- James Yersh, BlackBerry’s former chief financial officer, is now Chief Administrative Officer at eSentire.

- Saibal Chakraburtty, who spent four-plus years at BlackBerry in a variety of management roles, would become Arctic Wolf’s Director of Product Management.

Kim Tremblay, co-founder

and former Senior Vice-President

of Strategy at Arctic Wolf Networks

(Photo courtesy of Arctic Wolf Networks)

People like them, all ex-BlackBerry, are now the backbone of the Waterloo cybersecurity ecosystem.

Concurrently, other once-removed branches on the cyber family tree appeared. Arctic Wolf CEO Brian NeSmith points to three main ones: Blue Coat Systems, Waterloo network optimization company Sandvine, and eSentire. And all of them share in common a connection to University of Waterloo.

Blue Coat was founded in 1996 as a company called CacheFlow by University of Waterloo computer science professor Michael Malcom, Joe Pruskowski and Doug Crow. It would eventually be folded into U.S. software company Symantec, but not before NeSmith was brought aboard as CEO in 2000. NeSmith and Kim Tremblay, a UW math and computer science graduate who also worked at Blue Coat, later formed Arctic Wolf (Tremblay retired earlier this year).

Sandvine grew out of PixStream, a company whose core team was groomed at Hewlett-Packard. PixStream and Sandvine personnel now populate a host of Waterloo companies, many of them cybersecurity companies or companies that depend on cybersecurity. PixStream and Sandvine co-founder Marc Morin, for example, would go on to found and lead Auvik Networks. Sandvine CTO Don Bowman founded and now leads a 20-person startup called Agilicus, which aims to protect the networks of cities and towns.

Don Bowman, former Sandvine CTO, now leads Agilicus, a security

startup in Kitchener, Ont. (Communitech photo: Anthony Reinhart)

Sandvine, says Bowman, drew on personnel and expertise from CacheFlow, later known as Blue Coat, and which played a role in the genesis of Arctic Wolf, which, in turn, has roots leading to UW.

As for eSentire, which has 750 customers and US$6 trillion in assets under its protection, it was founded in 2001 by Eldon Sprickerhoff, who happens to hold a math degree with a major in computer science from, as you might have guessed, University of Waterloo.

It seems incongruous, at first, that a company which got its start as a University of Waterloo research project aimed at indexing the Oxford English Dictionary, should today have cybersecurity at the core of its product suite.

Then again, it stands to reason that a company like OpenText, which brands itself as a leader in information management, should be interested in keeping that information secure.

To that end, last February, OpenText subsidiary Webroot issued its annual comprehensive summary of cyber threats. The findings are, as you might expect, alarming.

- A 640-per-cent increase in phishing attempts in the previous year

- That one-in-four malicious URLs are hosted on otherwise non-malicious sites

- That 8.9 million URLs were found hosting a crypto-jacking script

- That top sites targeted by cybercriminals are Facebook, Microsoft, Apple, Google, PayPal and DropBox

- That crypto exchanges, gaming sites, web email, financial institutions and payment service sites were among the top five targeted in phishing attempts

- That malware targeting Windows 7 increased by 125 per cent

- That consumer PCs are twice as likely to become infected as business PCs.

Since the pandemic began, cyber attacks have not ceased. Quite the opposite.

U.S., U.K. and Canadian security officials warn that Russian cyber players are deliberately targeting organizations working on COVID-19 vaccine development. In August, the Canada Revenue Agency was hit with two cyberattacks that breached thousands of accounts, forcing it to temporarily shut down its online services and suspend applications for COVID-19 benefits.

Bowman says that a development like a pandemic – or any big news story – becomes a natural magnet for hackers, who leverage fear for their own gain.

“Anytime there's something in the news, there's always phishing around that,” he says. “There’ll be like a natural disaster somewhere and there’ll be a bunch of scams that are related to it. It naturally attracts that sort of thing.”

Bowman also says that COVID-19 generated conditions ripe for exploitation. At the outset of the pandemic, millions of workers were suddenly operating out of their homes, often without the protections offered by their companies’ servers and IT departments.

“That shift – the largest home deployment of people in history – was unprecedented,” he says, adding that people by and large are inclined to trust, to receive an email request and treat it as legitimate, even when it isn’t.

“So I think that naturally, the criminal elements out there, they recognize systematic weaknesses.”

That’s where companies like eSentire come in. For many firms, particularly if they don’t have the scale of thousands of employees, it’s far more cost effective and secure to outsource cyber protection to a company like eSentire rather than build measures in-house, hire a security team, and then configure and operate a security system 24/7.

“That's a very daunting task,” explains J. Paul Haynes, eSentire’s President and COO. “Many companies just say, ‘This isn't our lane, we’re never gonna be experts in this; we don’t generate our own electricity and so I don’t know why we would think we can do a better job at cybersecurity.’ So then they look to service providers like ourselves.”

When the pandemic lockdown began, most of eSentire’s SOC staff began operating from home, something that was accomplished, Haynes says, with a relatively uneventful “flick of a switch,” thanks to redundant remote measures the company had put in place, at the cost of millions of dollars, a year ago last spring as a safety hedge, prior to eSentire’s move from Cambridge to Waterloo.

In at least one respect – namely, talent – operating in a pandemic has had an advantage: The company’s prospective talent pool has expanded beyond Waterloo Region’s borders.

“We see the distributed world working far more effectively than anybody would have predicted,” says Haynes. “We are super effective in this mode, which now for us gives us a broader [hiring] aperture. If somebody wants to live up in Timmins, as long as they have an internet connection, then they’re probably a candidate to work for us if they have all the other skills.”

As the era of the Internet of Things and autonomous vehicles leads to ever more devices and infrastructure connected to the internet, and as artificial intelligence is harnessed by cyber criminals, the threat to machines, data, infrastructure and security only grows.

But what keeps Lewis Humphreys up at night is something far more dire.

Lewis Humphreys, founding Managing Director of the Cybersecurity ]

and Privacy Institute at University of Waterloo, during a workshop at

Communitech’s 2019 True North conference.

(Communitech photo: Harminder Phull)

Humphreys, the founding managing director of a unique University of Waterloo organization called the Cybersecurity and Privacy Institute, is worried about what he calls “the storm” – the massive worldwide cyber assault now under way on not just computers and information, but on the foundations of democracy and the world order itself, concerns that have heightened amid the Black Lives Matter movement and the looming U.S. election.

Surveillance capitalism. The monetization of personal data. Fake news, and gaslighting, aimed at destabilizing governments. State-sponsored viruses designed to cripple defence infrastructure. Attacks on corporate and financial giants intended to frighten investors and rock economies – think Facebook and Cambridge Analytica, think Russia, think North Korea and China.

“The main thrust of my work is to build ethics and morality into the training of cyber-security and privacy professionals in a way that it hasn't been done anywhere else,” says Humphreys. “That's why I'm here in this spot.”

Humphreys grew up in Georgetown, Ont., studied political economy at the London School of Economics and was eventually hired by the University of Arizona to manage the intellectual property generated by the school’s massive US$600-million research budget.

The Cybersecurity and Privacy Institute, which exists to improve information security and human privacy and to advance UW as a leader in cybersecurity and privacy research, hired him in 2017.

“When I saw that Waterloo had created this Cybersecurity and Privacy Institute, I felt like my background, my passion for these issues, was a kind of perfect fit.”

Humphreys thinks that multicultural, pluralistic, social-democratic Canada, and barn-raising, do-the-right-thing, tech-for-good Waterloo Region, is precisely the place from which to turn back the storm.

“I think that there's a huge opportunity for Canada to offer products and services and companies that don’t have the geopolitical baggage that all these other companies do,” he says. “I think that this is actually something that we should be talking more about, and that it should be central to a national security strategy.

“And we’re right in the centre of it here in Waterloo, and likely the company and companies that would [lead] that would be the BlackBerrys, the eSentires.”

Perhaps they already are.

Michelle Stainton of Your Girl Friday says that when she gets a request from a customer, there’s only one correct answer and that answer is “no problem.”

And so, when the day came that Stainton received a request to locate and purchase “a coffin,” she didn’t so much as skip a beat.

“I said, ‘Are we talking halloween or your grandmother?’” It turned out to be the former.

Stainton’s business is based on helping busy corporate employees by running errands for them. The tagline on her email is, “The ultimate employee perk.”

One of her most important clients is eSentire, whose employees, whether they’re working from home or from the company’s security operations centre, often can’t afford to risk ducking out at lunch to pick up groceries for dinner – or coffins for halloween. Doing so might mean a virus cripples the network of an eSentire client. And that simply can’t happen.

So, Stainton does it all. In the pre-pandemic era, that meant lunch orders, groceries, automobile oil changes, tire swaps, diapers for the kids. Since the pandemic hit, her services have been modified and scaled back somewhat, and also include curbside delivery.

But the bottom line hasn’t changed: “Whatever they need that alleviates stress and increases productivity for their team,” says Stainton.

Stress, says SOC senior analyst Jack Fahel, is part and parcel of the job. Particularly for a new hire. Particularly the first time a new threat is encountered. Particularly when the threat emerges at 3 a.m., when it’s more difficult to contact a client company about steps they need to take to protect themselves.

“Eventually you learn and sort of get used to the process,” he says.

Breanne Sharpe, SOC technical lead, says a SOC analyst is never on duty alone. Threat resolution can be quickly escalated by a team, if necessary, something that’s true even when working from home: Messaging platforms and video links replace face-to-face contact.

“Everyone in the SOC is very friendly, very open, very receptive to answering questions,” she says.

Sharpe, Fahel, none of them ever met Bill Tutte, who died in 2002. But his presence and legacy looms large in eSentire’s operations.

“The origin story, like so many other tech companies in the area, really starts with University of Waterloo,” says Mark McArdle, eSentire’s former chief technology officer and now a cybersecurity consultant. “[UW] has sprung an entire ecosystem of cybersecurity around the globe.”

When they would hike and walk along the Grand River, talking about flowers and astronomy and, sometimes, the British royal family, it was never lost on Dan Younger that at his heart Tutte, a man whose professional life revolved around numbers, was a gentle, curious soul with a poet’s gift for observation.

On the fifth floor of the University of Waterloo’s math building, a short walk from Younger’s office, is a memorial to Tutte, replete with his Order of Canada citation displayed in a glass case and an inscription posted on the wall:

The University of Waterloo dedicated a road on campus to Bill Tutte in

2017, the centenary of his birth. (Communitech photo: Anthony Reinhart)

“What is mathematics? You seem to have three choices. Mathematics is the Humanity that hymns eternal logic. It is the Science that studies the phenomenon called logic. It is the Art that fashions structions of ethereal beauty out of the raw material called logic. It is all of these and more. Much more, I can assure you, for mathematics is fun.” – William T. Tutte.

So. Is Bill Tutte ground zero? Does Waterloo Region’s existing cybersecurity ecosystem owe him a debt?

“Absolutely,” says Younger. “There’s no question. I mean, all of that work is combinatorial mathematics and he came here as the proponent of combinatorial mathematics, and his actual experience was the experience which he had in developing methods for codebreaking.”

A giant?

“Without question.”