Four decades ago, a tech whiz named Jerry Krist launched a new venture in the basement apartment he shared with his wife in Waterloo.

It was the dawn of the personal computing era, and Krist, who had a knack for building hardware as well as software, called his company Northern Digital. It was among the first startups to spin out of the University of Waterloo, a still-young institution already known for its pioneering work in computer science.

Along with Watcom and Dalsa, Northern Digital would help pave the way for the more than 1,600 companies that now make up Waterloo Region’s globally recognized tech ecosystem.

Today, Krist’s creation – known as NDI – employs more than 250 people and creates the optical measurement and electromagnetic tracking technology that enables surgeons around the world to carry out less-invasive surgery on brains, hearts, spines and other delicate parts of the human body.

“We provide that navigation or positioning of a tool relative to a patient in a phenomenally accurate way,” says President David Rath. “The most exciting thing from our perspective is it enables surgeries that couldn’t have been done before.”

The NDI of today, headquartered in a north Waterloo busidness park dotted with tech companies, is a long way from that basement apartment at 50 Central St. in the city’s old core, next to Waterloo Park. That’s where Krist, working at a table with his wife, Ludmila Sokolova, soldered parts and built the company’s early PCs

.jpg)

Jerry Krist and Ludmila Sokolova built Northern Digital's first computers in their basement apartment

in this building at 50 Central St. in Waterloo. (Communitech photo: Anthony Reinhart)

“The beginnings were difficult,” Sokolova recalls. “There was no money and every cent we had went into the company.”

Back in 1981, Northern Digital was the natural outgrowth of the computing world’s evolution beyond bulky, room-sized mainframes and into personal desktop machines, an evolution that UW, with its focus on hands-on teaching and learning, was helping to lead.

Krist was part of the university’s drive to provide more of these new, smaller devices to enable the growing number of computer science students to write code, test it and fix problems quickly. UW needed something that packed more memory and could handle more sophisticated programming languages than the hobbyist-style personal computers of the day, models like the Apple ll, Commodore PET and Radio Shack TRS-80.

The school’s renowned Computer Systems Group (CSG), which rented space in a small bank building at University Avenue and Phillip Street, took up the challenge in 1980. While several professors led software development, they assigned the hardware tasks to Krist.

“He was a software guy but he always had an interest in hardware,” recalls Jim Welch, a friend, fellow member of the CSG team and former UW professor. “He could see a problem and then develop a solution for it. A lot of these problems were novel problems that no one else had ever attacked before.”

Like his approach to solving problems, Krist had an eclectic range of talents and passions. He ran varsity track while he was a math student at UW, sang in choirs and musicals, played the piano, and built things, from leading-edge electronics to his own house in Waterloo.

When the university wanted to connect high-end IBM printers to its fleet of PDP-11 computers, it was Krist who created a connector device that “pretended” to be an IBM 360.

When the CSG created a mobile teaching computer – a rolling tank affectionately called the WATCOW – it was Krist who ventured over to the university machine shop to build a trolley cart sturdy enough to wheel the hefty beast around.

And when Wes Graham, the late and legendary “father of computing” at UW and a water-ski enthusiast, wanted to pioneer automated scoring technology for the 1979 international water-ski championships in Toronto, it was Krist who built the hardware for both the measuring system and the scoreboard.

“Jerry was our go-to guy for hardware,” says Don Cowan, Director of the Computer Systems Group and the first Chair of UW’s Computer Science Department. “He was a nice guy. A bit quirky in his ways, quite opinionated in how things should be done and quite often was right.”

Graham, known as much for his thrift as for his vision, wanted a microcomputer that could make use of the university’s existing fleet of keyboards and monitors – “dumb” terminals that had previously connected students to the university’s hulking IBM mainframe

Rear view of an early MICROWAT computer, Northern

Digital's first product. (Photo courtesy Mike Naberezny)

Working out of the second floor of the bank building at University and Phillip, the CSG developed a working prototype by December 1980. Called the MICROWAT, it was built around a then-powerful Motorola 6809 microprocessor and a number of expansion cards, or circuit boards, that increased memory capacity and efficiency, and integrated all the components. Most importantly, it could run software developed by the CSG, which in turn enabled the MICROWAT to run FORTRAN, APL, COBOL, BASIC and other programming languages – essential for UW’s hands-on approach to teaching computer science.

While working on the prototype, Krist made a pitch to Graham to start building multiple MICROWATs on contract. The university had promised to sell one of the new microcomputers to IBM’s research labs in New York, and Graham was hopeful that enough MICROWATs could be built over the next 10 months to be used for CS250, a programming course for undergraduate students.

“As we were eager to get involved with IBM quickly we decided to go along with Krist’s suggestion,” Graham wrote at the time. “A contract was drawn up with Krist which gave Krist and U of W equal rights to pursue the product of the work as each saw fit.”

In addition to the prototype unit, Graham contracted Krist to produce another two MICROWATs right away, with the possibility of another 32 units or more in the coming months.

Inspired by the order, Krist launched Northern Digital in early 1981.

“This was (Northern Digital’s) first gig, to build MICROWATs to be used at the university,” former CSG staff member Trevor Grove said during a 2017 presentation on the Commodore SuperPET, which UW helped design based on its learnings from the MICROWAT project.

Despite the university’s belief in the MICROWAT design, Krist ran into delays in productizing the hardware. As winter turned to spring, Graham and others worried that they wouldn’t have enough units ready for the fall 1981 class of CS250.

At about the same time, UW began looking at how it might enhance the Commodore PET PC to run programming software developed by the CSG. A production-ready add-in board was developed and the university decided to switch horses and ride forward with what became the Commodore SuperPET.

Although the MICROWAT lost the race, Northern Digital built as many as 100 units, which the university put to use alongside the SuperPETs for a number of years. Advances in technology, and the arrival of IBM PCs, eventually pushed both to the sidelines

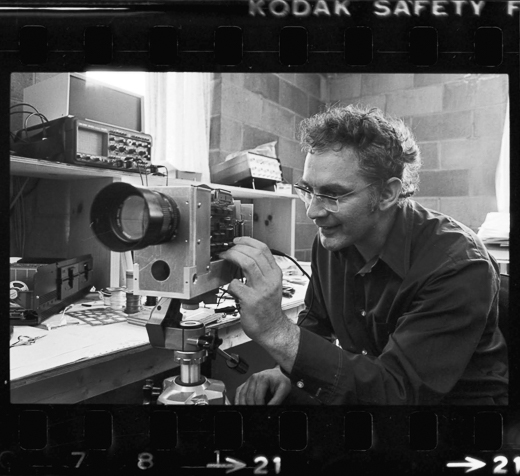

Jerry Krist with an infrared camera in 1983. (Photo: Kitchener-Waterloo Record

Photographic Negative Collection, University of Waterloo)

Meanwhile, Krist began casting about for new projects. His work on the water-ski measurement hardware back in 1979 had kindled a passion for integrating cameras and digital technology.

His friend Jim Welch recalls that Krist developed a product that sorted various kinds of lumber coming off a conveyor belt and directed the pieces into the appropriate bins, and another device that performed a similar task to sort the quality of wood that went into parquet flooring.

As the company grew, Krist moved it from the basement of 50 Central St. to rented space near UW at the corner of Columbia and Phillip streets, and then to its own building at 403 Albert St.

In a precursor to NDI’s business today, he also began refining Northern Digital’s focus, concentrating on precise optical measurement systems. During the 1980s and 1990s, the company’s evolving technology was used in a range of research applications, from medical procedures to industrial wind tunnels for testing Boeing aircraft and robotics applications that tested the robotic Canadarm for use on NASA space shuttles.

Krist’s passion for the workshop shines through in a 1991 K-W Record article in which he explained why NDI did so much prototype-making in-house.

“You can’t do R&D without having the facilities,” he said. “Having a machine shop tremendously enhances our ability to invent and develop things.”

His former wife, Ludmila Sokolova, says Krist’s intense drive to succeed as an entrepreneur was likely forged in his youth. Born in Amsterdam in 1946, his family moved to Canada when Krist was seven to escape the devastation caused by the Second World War.

“He had to prove himself,” she recalls. “He always wanted a company and a title.”

The demands of running a business took its toll on the marriage, and the couple parted ways.

“I think it was too much for Jerry. Two children came, the house, the company – he must have been overwhelmed, he hardly ever slept. I am sure the man... had lots and lots to deal with. Too much stress.”

In 1994, Krist gave up the day-to-day running of NDI after being diagnosed with cancer. Four years later, he sold the company to a group of senior employees.

Around this time, he “fell in love with a front-end loader” and devoted himself to the organic farm he owned in the countryside west of Waterloo, says Welch.

“He decided that he would go into pig farming because he was overjoyed that he could buy a pig farm and get a front-end loader. I’d visit him and he’d say, ‘Welch, you ought to sell all your software investments and get yourself a pig farm.’ And I’d say, ‘Jerry, I went to university so I wouldn’t have to be a pig farmer.’ But he really enjoyed it.”

Krist died in 2003 after fighting cancer for nearly a decade.

NDI continued to evolve. In 2011, the ownership team sold the company to Roper Industries Inc. (now Roper Technologies), a publicly traded company based in Florida that owns a number of technology subsidiaries.

As the medical technology industry has grown over the past decade, NDI has focused more on surgical navigation systems. In 2020, the company decided to step away from its industrial applications and focus solely on the medical industry.

“My management team and I spend a lot of our time thinking about strategy and markets and where we can be successful and where technology will be successful,” says David Rath, the current president. With the rapid growth in medtech, NDI “needed to focus on that area more heavily in order to continue to drive that success and be the partner that we wanted to be for OEMs (original equipment manufacturers).”

The medical market is “a pretty wide space and we’re excited about growth,” Rath says. “We’ve been very fortunate over the 40 years to be continually growing – a pretty phenomenal financial success story. We're excited about that and the future.”

Just as Krist focused on problem solving, Rath says one of the secrets to NDI’s longevity is its commitment to listening to customers and satisfying their needs. NDI staff regularly talk to their clients – the original equipment manufacturers that make surgical tools – as well as to surgeons and medical researchers to better understand their challenges and requirements.

“You have to be very mindful of the marketplace around you and listen to your customers more intently than you think you need to,” says Rath, who studied systems design engineering at UW before earning a master’s degree in medical biophysics from Western University.

NDI says that 90 per cent of North American surgical navigation systems use its optical measurement technology, and more than 800 universities worldwide use NDI products. The company, which conducts a great deal of original research, also says that NDI papers have been cited more than 25,000 times in the research work of others.

“We are driving innovation and driving technology patents all the time,” says Rath. “IP portfolios are a significant asset from our perspective… it creates a barrier of entry for competitors, of course, but it also enables our OEMs to understand what is out there that is possible, and it really creates an avenue for conversation.”

Rath, who has been with NDI since 2004 and president since 2012, says Waterloo continues to be the best place for the company’s home base, just as it was for Jerry Krist all those years ago.

“We have just had a fantastic track record and relationship with the community,” he says, citing access to talent and relationships with nearby universities. “We just re-upped on another lease on a new building, so we’re definitely here for the long term.”