If you don’t believe that a building can have a destiny, that bricks and mortar and polished wood have a preordained fate, meet Gord Miller.

His entire working life – nearly half a century of local history, if you want to know – is entwined with the events that have unfolded at 14 Erb St. W. in Waterloo, and there’s no arguing with history, is there?

But let’s start with the here and now.

In a matter of weeks, on May 11, 2017, Communitech will throw open the doors on Waterloo Region’s new Data Hub – at 14 Erb West.

The renovated, stately, historically designated structure will, among other things, house Canada’s Open Data Exchange. It’s intended to be a communal space – nearly 20,000 square feet – where startups, medium-sized companies and large enterprises can mine and augment the potential of big data – the numbers that drive artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things and the algorithms behind many of today’s cutting-edge tech companies.

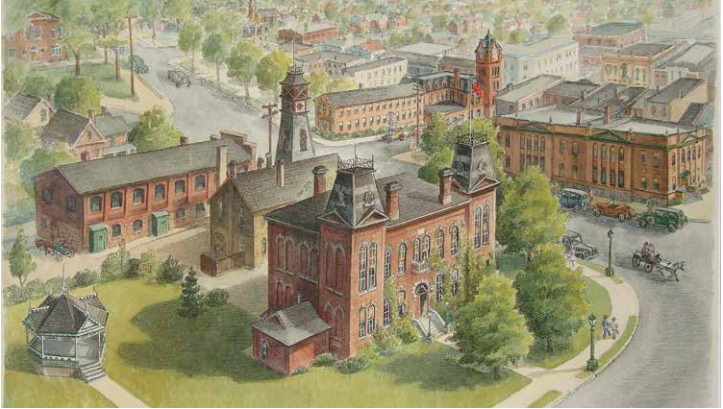

The corner of Albert and Erb streets, circa 1915. At left is the former Waterloo town

hall, and to the right, the offices of Dominion Life at 14 Erb. St. W., soon to

be Communitech’s Data Hub. (Image: City of Waterloo)

The bet is that doing so will inject additional energy into the region’s already bubbling tech scene. The side bet is that the building will once again augment the civic vibrancy of the area, just as it did 137 years ago, in 1880, when it first opened for business.

“I can think of very few other [buildings] that are as important or have played as prominent a role and therefore would be as historically as important as that one,” says local historian and retired University of Waterloo professor Ken McLaughlin.

When it was built – fronting Erb, at the corner of Albert Street – the building was situated at the very heart of the growing town of Waterloo. The town market and fire hall sat just to the north, where the Waterloo Public Library is today. Across the street was the town hall, with a small gazebo directly opposite on the corner, making the intersection the town’s main gathering point for civic celebrations, like the one in 1918 to mark the end of the First World War.

“That corner, in which that building is the centrepiece, really represented the life and times of the city of Waterloo,” says McLaughlin.

And it was here, at No. 14, that a long line of insurance companies, including the predecessors of Sun Life and Manulife and Economical, underwrote the policies that would help lay the economic foundation of the region. It was here that those same insurance companies became the original purveyors of big data, accumulating the numbers and statistics that would buttress their businesses and build into the field of actuarial science.

Residents of Waterloo celebrate the end of the First World War, on Nov. 11, 1918, at

the corner of Albert and Erb streets – a popular location for civic celebrations and

gatherings. (Credit: Waterloo Public Library)

It was those same insurance companies, in the early 1960s, that nudged the then-fledgling University of Waterloo to broaden its co-op program beyond engineering to a new discipline called actuarial mathematics, and quickly from there into a new program called “computer science,” all to feed a tech talent gap as they rapidly adopted the latest technology of the day.

Sound familiar?

And that’s where Gord Miller’s story with 14 Erb begins.

In 1963, Miller, then a boy of 17, joined the Canada Health and Accident Assurance Corporation, the then-resident of 14 Erb West. His job was in the burgeoning field of tabulating, the precursor of computing.

It was Miller, with a team of four others, working in shifts 24 hours a day in the north-east corner of the building, who loaded all the data from the firm’s old tabulating machines onto the company’s first, real computer, a beast larger than a closet called a Remington Rand UNIVAC 1004.

The 1004 weighed 2,500 pounds and had a then-whopping memory of 721 bytes. For comparison, consider that there are more than a billion bytes in a single gigabyte and the smallest memory available today on an iPhone is 32 gigs. The 1004 cost nearly half a million U.S. dollars in today’s currency.

“When we got the 1004, what a blessing,” says Miller. “It was such an advancement.”

The corner of Albert and Erb streets was the focal point for a growing community.

Waterloo’s town hall is in the foreground. Behind it, the fire hall, and behind it, the

market. At right is 14 Erb St. W., soon to be Communitech’s Data Hub. (Image:

Woldemar Neufeld, Bird’s Eye View of the Town Square c. 1975-1977; watercolour & pen

and ink, 52 x 77 cm; Collection of Wilfrid Laurier University)

But transferring the data from the tabulating machines to the computer was no small feat. “We couldn’t leave the building,” recalls Miller. “It took the five of us a week-and-a-half to put all that information on the new system.”

Two years later, in November of 1965, Miller was at work, looking out a west-facing window as a funeral procession made its way along Erb and turned up Albert street. The then-chief of police, Lloyd Otto, had died. As the officers marched past, Miller turned to one of his insurance colleagues, a small man named Del, and said, “I want to be one of those guys.”

A year later, Miller was one of those guys, a rookie constable with the then-City of Waterloo’s police service. And because this is a story about a building where all the the cosmic tumblers click perfectly into place, it was Miller, in 1987, having risen through the ranks, who heard through his insurance contacts that 14 Erb West was coming up for sale.

He called his chief, Harold Basse, knowing the force – which had since become the Waterloo Regional Police – was looking for a site for a new station. “Leave it with me,” said the chief.

And, naturally, in 1991, when the new police station opened at 14 Erb West after extensive renovations that preserved the building’s fine woodwork and intricately decorated ceilings, it was none other than Miller who became the station’s first divisional commander. Those cosmic tumblers at work once again.

“I’d been working as an officer in the station next door, and when we moved in here in ’91, I remember [Regional Chair] Ken Seiling saying, ‘Staff Inspector Miller, you haven’t gone very far in your career. From over there, to over here.’ ”

Even as a police station, the building retained a tie to the world of data that first gave it a reason to be. On the main floor you’ll find a steel-shrouded vault, guarded by an eight-ton steel door that’s nearly a foot thick.

“All the insurance companies kept their stocks, bonds, and silver and gold bars in that vault,” Miller recalls. “At the start of the day, it took four people to open [that] door. It had four different combinations that they had to undo before [it would open].”

When the police took over as residents, the vault was used to house the backup computer tapes that ran the city’s traffic lights. Think of it as IoT, 1.0.

“We knew that in the event of a fire, those tapes would be safe.”

A year after the station opened, Miller was promoted to deputy chief and had to give up his 14 Erb West residency. He retired from the police service in 1998.

“It was rough [when I left]. I didn’t want to leave here,” he says.

14 Erb St. W. was the home of Dominion Life Assurance from 1912 to 1954. The

company would later be acquired by Manulife. (Image: Waterloo Public Library)

“I have such good memories of this building, in the police service and the insurance business. It was a majestic building.”

In 2013 the building was sold to Ophelia Lazaridis, wife of Mike Lazaridis, of BlackBerry fame, for a reported $3.1 million. Communitech has rented the space and will make it available to companies eager to explore the possibilities of big data.

“I am absolutely delighted to see it playing [a new role as a data hub],” McLaughlin says. “It’s got a great role to play. It’s right there in the centre [of town]. [It will be] on the new LRT [route], linking to the university on one side, and [the] Communitech [Hub] on the other, tied in minutes to both places.

“That building has so much historical significance and is so central to the life of the community. It was really the central business section of the city and town for such a long time. And this was probably the most imposing building in that business section for probably 100 years.

“So, if you see it that way, it’s pretty significant. That building, with its pillars at the front … it has a sense of style and elegance and class to it.

“And it still does. It has presence and a sense of architectural detail. Very little else in Waterloo did in those days. That building was always very centrally important.”

As it now will be, once again.

“What other building in the city of Waterloo has so many links to the past and present as that one? I can’t think of any.”