Waterloo Region, September 29, 1993. It’s early morning when local entrepreneur Yvan Couture begins pitching an idea to a crowd gathered at the University of Waterloo’s William G. Davis Centre for the monthly meeting of the Computer Technology Network.

Couture, then founder, President and CEO of Taaz Corporation, a consulting firm serving the tech community in southwestern Ontario, is jazzed about the growth opportunities he’d seen industry associations provide to techies in places like Ottawa and Raleigh, North Carolina – peer-to-peer training, mentoring, conferences – and has built out a similar plan for Waterloo with the help of Ruth Songhurst, then president of Mortice Kern Systems (MKS), a local software firm.

Using appliqués on an overhead projector, he begins to tease out a vision for a member-funded organization that would “provide the vehicle for assisting the local technology sector to prosper and become the main driving force in the local economy, as well as enhancing Waterloo Region as a hotbed for world-class technology.”

The roomful of entrepreneurs is more interested in the free doughnuts and coffee than anything Couture has to say.

“It fell very flat,” Couture says with a laugh. “One of the key guys was adamant that there was no way that anybody would pay, so it kind of died. It didn’t go anywhere.”

Well, not yet.

A few years earlier, the Atlas Group, an informal assembly of local tech executives, begins to meet regularly over breakfast at the corner of Phillip and Columbia streets in Waterloo to help each other navigate the C-suite. Its early, ever-changing roster includes Couture and the likes of Randall Howard (MKS), Jim Estill (EMJ Data), Tom Jenkins (DALSA, before OpenText) and Jim Balsillie (Sutherland-Schultz, before Research In Motion).

“We were fledgling companies, none of us were very large.” – Tom Jenkins

“We were fledgling companies, none of us were very large,” says Jenkins, former CEO and current Chair of the Board at OpenText. “It was the very origins of all the Waterloo spinoffs. We were providing self-help amongst the CEOs and we started to realize that our staff really needed the same thing that we were getting from each other.”

Success got in the way of taking that next step – by 1996, Research In Motion and OpenText were well on their way to becoming international behemoths and on the cusp of going public, while other members of the Atlas Group wrestled with rapid growth.

Waterloo was quickly becoming central to the Canadian tech scene, with one of the best computer engineering schools in North America funnelling talent into local tech businesses, most of which were run by entrepreneurs whose egos never got in the way of helping one another succeed.

All that was missing was a communal voice to help spread that message on the national stage.

November, 1996. Recognizing the need to bring a bigger pipe into the community, local MP Andrew Telegdi and Waterloo Mayor Brian Turnbull convene a meeting to discuss ways to foster technology growth in the area, including the possibility of creating an association to help formalize the industry.

The idea wasn’t new to Couture, Jenkins or Dieter Hensler, then president and CEO of software firm Waterloo Maple, all of whom are in attendance. In fact, that thought had already given itself a name – the Waterloo & Area Technology Association (WATA) – and put its objectives on paper.

First and foremost, if formalized, WATA would “help provide an environment where technology companies in the CTT [Canada’s Technology Triangle] can grow to become more globally competitive, world-class, and profitable companies. In addition,” reads a document prepared for the November meeting, “it will help foster an environment that will be attractive to prospective employees as well as new and existing firms wishing to relocate here.”

Sound familiar?

“At that meeting, basically we asked, ‘OK, who’s in? Who wants to do this?’” says Couture. “We walked away and said, ‘We’re going to come back in a month. If we’ve found at least 10 other companies who are willing to put five grand in to do this, then we’re going to go ahead.’ In a month, we came back and we had something like 25.”

As that total continued to climb, it was officially game on. Couture credits Jenkins for convincing many of the original members to come aboard.

“He’s the one who would go to these companies and say, ‘Oh guys, you gotta follow ’em. You gotta follow, gotta follow ’em.’”

From banks such as CIBC and TD Evergreen, to firms like Whitney & Company and Gowlings, to the University of Waterloo and the University of Guelph, to tech companies including Research In Motion, Descartes Systems and Waterloo Maple, the mix of backgrounds – less than half were actually tech startups – and a willingness to collaborate brought strength to the table. But everyone had something to gain.

“Anybody who tells you that it was pure altruism is lying to you.” – Yvan Couture

“Anybody who tells you that it was pure altruism is lying to you,” says Couture, a sentiment echoed by Jenkins, who described the original impetus for an association as a kind of “mutual self-interest.”

“We believed that collectively we could become better individually,” says Couture. “Collectively we could be stronger because we’d have a stronger voice.”

At WATA’s first formal meeting on March 18, 1997, 18 of 23 founding organizations gathered at the University of Waterloo to begin the process of setting up a board of directors (every founding member was granted a seat), appointing a chair (Randy Fowlie of KPMG stepped to the plate) and finding a president/executive director to replace Yvan Couture, who was holding the position down until a candidate was selected from a pool of 40 applicants.

The standout contender for the gig was Vince Schiralli, a former IBM executive who was leaving Waterloo Maple.

“I was looking for an opportunity, but I clearly wasn’t looking at a not-for-profit organization,” says Schiralli. “I was on my way to something else. I’d had some very successful stints.”

As Schiralli recalls, his mindset shifted after a meeting on his deck with Yvan Couture. “I’m a natural sales and marketing guy, and I knew it was a sales job. It wasn’t going to be something that people were going to embrace. We had a real nice core group of founding members – especially Tom, and Jim [Balsillie], Yvan and [John] Whitney – but we wouldn’t have survived with just those 40 companies. We needed a lot more.”

Later, after a few bottles of red wine and some arm-twisting in Tom Jenkins’ kitchen, Schiralli was finally convinced: He was the right man for the job. On April 29, 1997, an offer letter was sent his way and he was announced as the first president at a board meeting in May. By June, the association would have 47 members.

Schiralli started his new gig in a corner of Taaz Corp.’s offices, down the hall from Couture. Almost immediately, the name WATA was jettisoned.

“It sounded too soft,” says Couture.

In its place, on a Friday afternoon after a couple of in-office brews, came the portmanteau Communitech.

“It felt right immediately,” says Schiralli. Community was the core principle; technology was the focus. That’s when Schiralli’s sales skills kicked into overdrive.

“When you believe in something, it’s easy to sound convincing.” – Vince Schiralli

“My strength, I think, was in my willingness to talk to anybody,” he says. “I had a real passion. I really believed in this. I really, really did. When you believe in something, it’s easy to sound convincing.”

From a blowout launch party (where Schiralli was photographed with a rocket strapped to his back) to golf tournaments and rowdy Oktoberfest parties to the development of early programming, talks and breakfast meetups, the Communitech brand began to grow.

“We made the programs simple, we made them inclusive, they were networking-based,” says Schiralli.

The widespread peer-to-peer mentoring that the Atlas Group envisioned for staff became real. “All of a sudden we had a peer-to-peer for presidents, for CEOs, for VPs of sales, for HR, and it just grew, and grew, and grew. We sponsored them. We hosted them.”

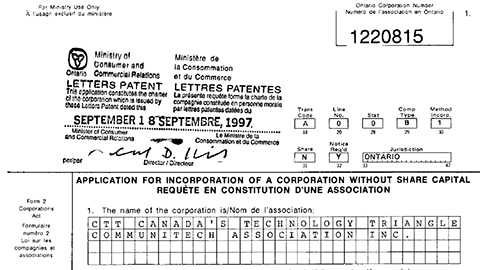

Communitech’s founding document from September 18, 1997

By the time Schiralli passed the torch on to Greg Barratt in 2000, he’d managed to increase Communitech revenues from $400,000 in year one to upwards of $1.2 million in year three. His team of 15 had outgrown their makeshift digs at Taaz Corp. and had taken up space at Conestoga College’s Waterloo campus. Growth seemed to come quickly, but it didn’t come easily.

“Communitech had a very tough evolution because it had to be democratic, it had to be by the entrepreneurs,” says Jenkins. “We gradually caught on to the fact that the accountants, the lawyers and the bankers – and then later on, once the industry started to mature, the venture capitalists – started to become the real backers of the association.”

Protections had to be built in to ensure that the tech founders remained in control of decision making. “We made sure that the organization’s governments always reported to the customer and the customer was always the entrepreneur. That’s why, to this day, Communitech and the majority of the board, is always made up of startups.”

The organization also had to learn to stand on its own two feet.

“We were completely funded by members,” says Couture, “so by the time we saw federal and provincial money, it was supplementary. It wasn't survival money, so in our DNA as an association, we had learned to be self-sufficient.”

By the time current President and CEO Iain Klugman landed at Communitech in 2004, the organization was ready for a new, more public-facing phase of growth.

“Greg Barratt had done a really good job at stabilizing the organization, then putting together some different revenue streams to ensure that the bills were paid,” says Klugman, who recently brought Barratt back to Communitech to serve as Vice-President of its Strategic Growth Team. “He put in place systems and processes, turned it into a really solid organization, so when I showed up it was in good shape…my job was going to be to put the place on the map and make it important to Canada.”

That started with a re-examination of the road Communitech had already travelled – on a macro level, what big opportunities remained to be seized? On a micro level, what barriers were its customers – tech companies – facing on a daily basis? How could Communitech make sure it had an ecosystem in place that would sustain a company from startup to going public?

The answer lay in a physical space: By moving into Kitchener’s former Lang Tannery in 2010, Communitech was able to engineer density in the region by becoming the physical hub of the Waterloo Region tech community.

“We really set out to build this place with a few principles, one of which was, ‘This is theirs, not ours.’” – Iain Klugman

“We really set out to build this place with a few principles, one of which was, ‘This is theirs, not ours.’ We didn't want a Communitech office,” says Klugman. “We wanted a Communitech Hub that belonged to the entrepreneurs and the innovators and the community, a place where everyone felt welcome and where no one was left behind.”

Twenty years after it launched, Communitech now fosters a community of more than 1,000 tech companies, from startups to rapidly growing mid-size companies and large global players. Waterloo Region’s startup density is now second in the world only to California’s Silicon Valley. In 2016, the region added 370 new startups and $341.6 million in private capital investment.

“I've travelled the world, and as a business model and an incubator network I would put Communitech, if not as the very best one in the world, it’s easily in the top five,” says Jenkins. “It's a community accomplishment. It's not any one person, it truly is a community accomplishment.”

Just don’t expect anyone to take credit for making it all happen.

“We do talk a lot about being humble and being the humble butler, and being here to serve,” says Klugman. “I've seen ego get in the way of success too many times, and especially in the type of business that we're in. We are a service industry. If we start to develop an ego, then we start to wander from what our mission is, which is to help.”

Twenty years after that ethos was set in motion, it still propels the Communitech ship forward.

Here’s to 20 more.